A History of Photographic Constraints

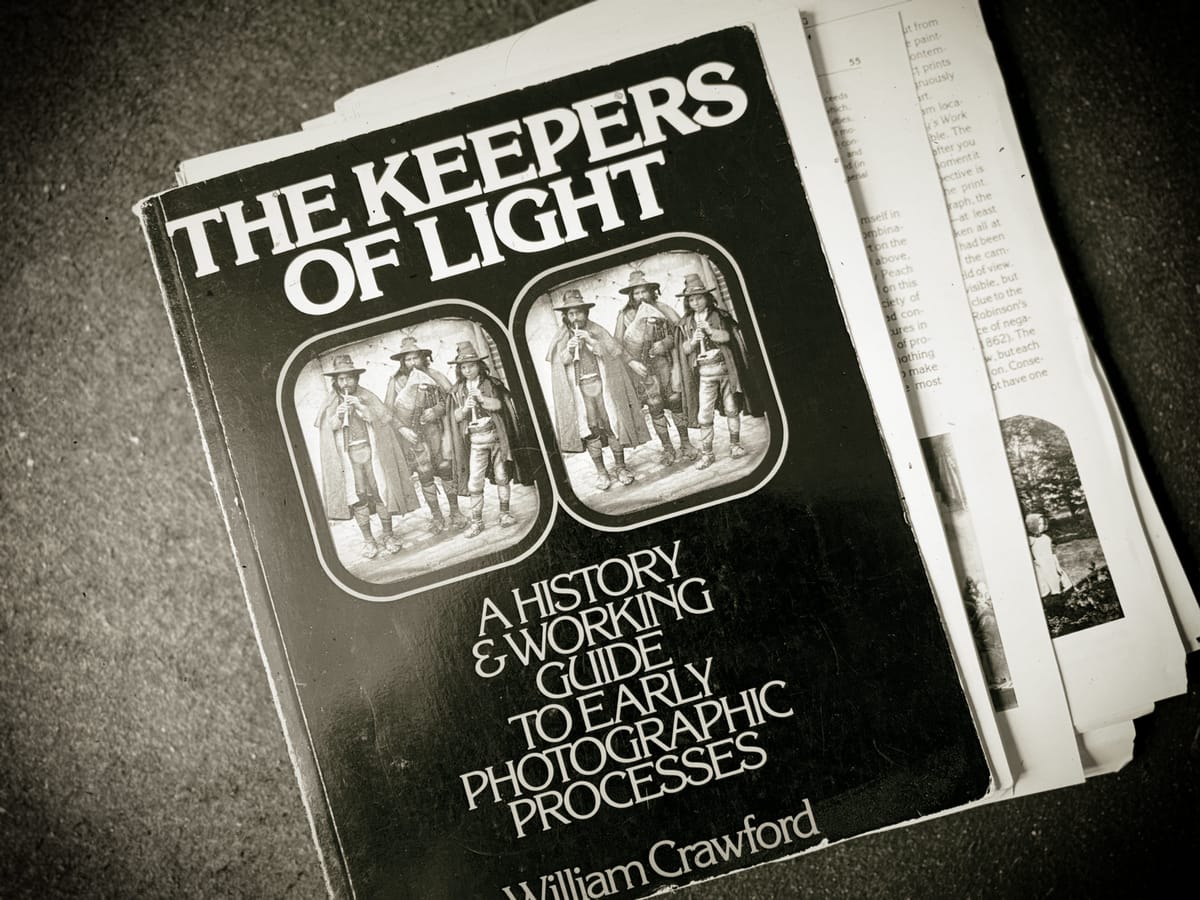

The Keepers of Light: A History & Working Guide to Early Photographic Processes

“The enemy of art is the absence of limitation.”

— Orson Welles

William Crawford‘s The Keepers of Light is unique among history books, chronicling—with a twist— photographic processes during their first century. The twist is that Crawford illuminates this history through the lens of technological constraint, using what he calls “photographic syntax” as its defining characteristic.

Syntax in linguistics is the “name for the rules of structure that make meaning possible” and likewise for photography as the set of technological constraints that defines what a photographer can communicate. With this as our mental model running through photographic history, we can see how the limits of current technology influenced what an artist could create:

Daguerre’s technique was used at first almost exclusively for landscape, architecture, or still-life scenes. The plates were not sensitive enough for portraits unless the sitter could be persuaded to remain motionless in bright light for many minutes. But by late in 1840, it was discovered that ‘accelerators’ or ‘quickstuff’…increased the sensitivity of daguerreotypes many times over. Together with the introduction of larger, faster lenses, this made portraits possible...

Imagine a time when making a portrait with the cameras of the day was next to impossible! Imagine, too, what wonderful art was made when with the barest of technological capability and think about how that is not eclipsed today when quite literally anything is possible.

Yet, The Keepers of Light is not a nostalgic book. It’s a book of innovation during a time when invention came from people, not corporations. It’s about the drive to make things better. Consider Sir John Herschel, a well known astronomer who also happened to invent cyanotype in his spare time, a process still used today:

Herschel was also the first to discover the photosensitivity of ferric (iron) salts. On June 16, 1842, Herschel read to the Royal Society a paper entitled, “On the Action of the Rays of the Solar Spectrum on Vegetable Colors, and on Some New Photographic Processes.” The new processes, for which Herschel coined the names cyanotype and chrysotype, were mentioned only at the end. The first part of the paper was about flowers.

It should be no surprise that in the age of gluttoness megapixels that many photographers still embrace film and chemical processes. Even though there are plenty of older photographers who took to digital and never looked back, they use our new processes understanding the discipline of their previous constraints, because constraint is a necessary condition for art.

Self-imposed constraints are a luxury, like a trust-fund kid living in voluntary poverty. Yet, the intent must be genuine as though the lack of constraint didn’t exist. As someone who strives to make art, I’m painfully aware that most all of the images I deeply love were taken by masters who likely couldn’t imagine how easy things would be in the future. It’s not merely quaint to see someone out with their large format view camera or clunky medium format camera when they could get a higher resolution image with a computer that fits in their pocket. These are not merely romantic notions or nostalgia, they are a discipline.

The second half of The Keepers of Light is about the processes themselves along with a section on conservation and restoration. I bought the book ahead of taking a class on platinum palladium printing and was surprised to find that the methods had mostly not changed, excepting for the fact that we now created our negatives for printing in Photoshop.

Published in 1979 and now in the public domain, there aren't too many good copies around, as far as I know. You can see mine in the picture fell apart as I was reading. Fortunately, The Internet Archive has it available to view in browser or download, though the downloads may be problematic (the ebook is poorly formatted).

The Keepers of Light is a book I cherish for its point of view and detail about a history that seems in even more relevant today than ever.

Books Mentioned